What happens in your brain when you’re in love?

You can’t eat. You can’t sleep. Your stomach and heart flutter when this person contacts you or suggests spending time together. Sounds like all the telltale signs you may be falling in love.

But what happens in your brain when you begin to feel lovestruck? And how does the brain change over time when it comes to love?

“Love is a biological necessity—it’s as needed for our well-being as exercise, water, and food,” said neuroscientist Stephanie Cacioppo, PhD, author of Wired for Love: A Neuroscientist’s Journey Through Romance, Loss, and the Essence of Human Connection (Macmillan, 2022). “And from a neuroscientific viewpoint, we can really say that love blossoms in the brain.”

Two decades of research has shown that when it comes to early-stage intense romantic love—the kind we often think of when we talk about being lovestruck—a very primitive part of the brain’s reward system, located in the midbrain, is activated first, according to Lucy Brown, PhD, a neuroscientist and professor of neurology at Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

Brown and her lab partners used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study 10 women and seven men who were intensely “in love,” based on their scores on the passionate love scale, a 14-item questionnaire designed to assess the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of passionate love that relationship researchers have widely used for decades.

People who score in the highest range of this assessment are deemed as being wildly, even recklessly, in love. Those who score in the lowest range have admittedly lost their thrill for their partner.

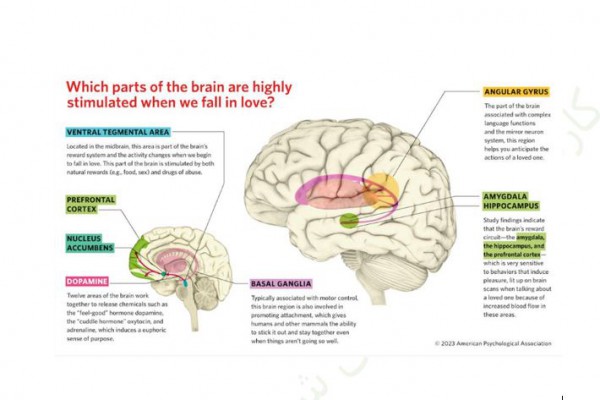

Participants in Brown’s study alternately viewed a photograph of their beloved and a photograph of a familiar person. When viewing the photo of their romantic partner, participants experienced brain activation in the midbrain’s ventral tegmental area (VTA), which is the part of the brain connected to meeting basic needs such as drinking when we’re thirsty and eating when we’re hungry.

“It’s the area of the brain that controls things like swallowing and other basic reflexes,” Brown said. “While we often think about romantic love as this euphoric, amorphous thing and as a complex emotion, the activation we see in this very basic part of the brain is telling us that romantic love is actually a drive to fulfill a basic need.”

Additional fMRI studies conducted by Cacioppo shed more light on how love affects your brain. Her team found 12 areas of the brain work together to release chemicals such as the “feel-good” hormone dopamine, the “cuddle hormone” oxytocin, and adrenaline, which induces a euphoric sense of purpose. Her findings also indicated that the brain’s reward circuit—the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex—which is very sensitive to behaviors that induce pleasure, lit up on brain scans when talking about a loved one because of increased blood flow in these areas.

While all of this is happening, Cacioppo noted, our levels of serotonin—a key hormone in regulating appetite and intrusive anxious thoughts, drop. Low levels of serotonin are common among those with anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders.

“This explains why people in the early stages of love can become obsessed with small details, spending hours debating about a text to or from their beloved,” she said.

How does longer-term love differ in the brain?

Once the initial excitement of new love has worn off and a couple becomes more committed, the activation areas of the brain also expand, Brown said. In studies among newly-married couples, Brown found parts of the brain’s basal ganglia—the area responsible for motor control—were activated when participants looked at photos of their long-term partner.

“This is an area of the brain heavily involved in promoting attachment, giving humans and other mammals the ability to stick it out even when things aren’t going quite so well,” Brown said.

Even among couples who have been married 20 years or longer, many showed neural activity in dopamine-rich regions associated with reward and motivation, particularly the VTA, in line with those early-stage romantic love studies. In a 2012 study in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, participants showed greater brain activation in the VTA in response to images of their long-term spouse when compared with images of a close friend and a highly familiar acquaintance. Study results also showed common neural activity in several regions often activated in maternal attachment, including the frontal, limbic, and basal ganglia areas.

Longer-term love also boosts activation in more cognitive areas of the brain such as the angular gyrus, the part of the brain associated with complex language functions, and the mirror neuron system, a region that helps you anticipate the actions of a loved one. That’s the reasoning behind couples who finish each other’s sentences or have a way of moving around a small kitchen cooking together without issue, Cacioppo said.

“People in love have this symbiotic, synergistic connection thanks to the mirror neuron system, and that’s why we often say some couples are better together than the sum of their parts,” she said. “Love makes us sharper and more creative thinkers.”

Can we find connectedness outside of romance?

It’s important to note that there are a variety of types of love that can benefit the brain, Cacioppo said.

A 2015 study in Science found mutual gazing had a profound effect on both dogs and their owners. Of the duos that had spent the greatest amount of time looking into each other’s eyes, both male and female dogs experienced a 130% rise in oxytocin levels, and both male and female owners experienced a 300% increase.

Other studies, including a 2020 review in Social Neuroscience, showed that face-to-face interaction and eye-gazing between mothers and their infants activated the brain’s reward system and increased gray matter volume in mothers, in an attempt to promote positive mother-infant relationships and increase bonding.

Even your love for a passion such as running, biking, knitting, or enjoying nature evokes activation of the brain’s angular gyrus, a region involved in a number of processes related to language, number processing, spatial cognition, memory retrieval, and attention, according to a study in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, led by Cacioppo.

“While the intensity of brain activity differs, the love between a parent and a child, a dog and its owner, or even one’s love for a hobby or passion, can provide the feeling of connectedness we are all looking for and that we need to survive as humans,” Cacioppo said.

Source

Related Posts