How Changes in Length of Day Change the Brain and Subsequent Behavior

Seasonal changes in light—longer days in summer, shorter in winter—have long been associated with human behaviors, affecting everything from sleep and eating patterns to brain and hormonal activity.

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a prime example: A type of depression related to diminished exposure to natural sunlight, typically occurring during winter months and more often at higher latitudes when daylight hours are shortest.

Bright light therapy has proven an effective remedy for treating SAD, plus maladies such as non-seasonal major depression, postpartum depression and bipolar disorder, but how seasonal changes in day length and light exposure affect and alter the brain at the cellular and circuit levels has kept scientists largely in the dark.

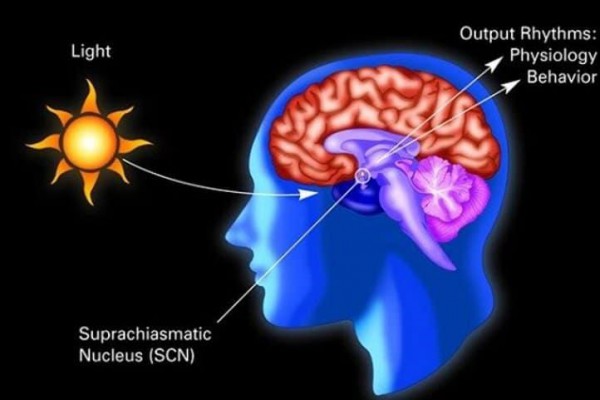

Tucked within the hypothalamus of the human brain is a small structure called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), each consisting of approximately 20,000 neurons. (The average human brain contains roughly 86 billion neurons and another 85 billion non-neuronal cells.)

The SCN is the body’s timekeeper, regulating most circadian rhythms—physical, mental and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle and affect everything from metabolism and body temperature to when hormones are released. The SCN operates based on input from specialized photosensitive cells in retina, which communicate changes in light and day length to our body.

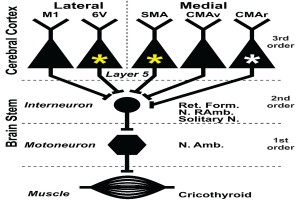

In the new study, Dulcis and colleagues describe how SCN neurons coordinate with each other to adapt to different lengths of daylight, changing at cellular and network levels. Specifically, they found that in mice, whose brains function similarly to humans, the neurons changed in mix and in expression of key neurotransmitters that, in turn, altered brain activity and subsequent daily behaviors.

“The most impressive new finding in this study is that we discovered how to artificially manipulate the activity of specific SCN neurons and successfully induce dopamine expression within the hypothalamic PVN network,” said Dulcis.

“We revealed novel molecular adaptations of the SCN-PVN network in response to day length in adjusting hypothalamic function and daily behavior,” added first author Alexandra Porca, Ph.D., a member of Dulcis’ lab.

The authors suggest their findings provide a novel mechanism explaining how the brain adapts to seasonal changes in light exposure. And because the adaptation occurs within neurons exclusively located in the SCN, the latter represents a promising target for new treatments for disorders associated with seasonal changes in light exposure.

Related Posts